#1: Ives – Sonata No. 2 “Concord, Mass., 1840-60” (1915)

Well, here we are at the end of the “Top 5” sonata-ranking journey. And though this is the fifteenth sonata I’m writing about, I think I’ve saved the best for last.

I’ve already written extensively about the Concord Sonata: in program notes for my junior piano recital in college in which I played the first movement, in lecture notes I prepared for my performances of the complete piece, and in another blog that was part of my classwork for an American Avant-Garde class in grad school. The piece has been very much on my mind recently, since I’ll be giving my tenth lecture-recital performance of it this week. So this will be sort of a culmination of thoughts from years living with the music. It’s been hard to organize said thoughts, so I’ll start with this quote from music critic Lawrence Gilman, in his review following the New York premiere of the piece:

“This Sonata is exceptionally great music – it is, indeed, the greatest music composed by an American, and the most deeply and essentially American in impulse and implication. It is wide-ranging and capacious. It has passion, tenderness, humor, simplicity, homeliness. It has imaginative and spiritual vastness. It has wisdom, beauty and profundity, and a sense of the encompassing terror and splendor of human life and human destiny – a sense of those mysteries that are both human and divine…”

It might sound like a case of overhype, but all of his sentiments are spot on. If you give this piece a careful ear, and especially if you get up close and try to play it, you’ll discover a world of fascinating harmony, rhythm, and emotion that seems to get more vast with each encounter. When I discovered it in high school, I struggled through the first listening but then slowly started to pick up on what was happening. As my fascination grew, I dug deep into the philosophical context of the piece, got a copy of the score, started playing through what I could, and that’s when I realized that this was a masterpiece.

Over years of attending concerts, Ives had been frustrated by what he perceived as a lack of depth and originality in works by American composers, an over-reliance on European Romantic influences and “safe,” consonant sounds. He had quietly been forging his own path, composing extremely dissonant, advanced music in isolation while working as an insurance salesman by day. And in the Concord Sonata, he laid out a sort of artistic manifesto and also created a robust piece of programmatic music. It’s a deeply philosophical work, to the extent that Ives even wrote a book (Essays Before a Sonata) to complement the piece, expressing his thoughts in words to better communicate with audiences. The essays have a meta quality: in the Prologue, he hits the reader with one weighty question after another, mostly about the idea of portraying concepts and/or concrete objects in music, posing these questions about evaluating the success of programmatic music even as he is writing an extremely highbrow programmatic piece.

Ives chose as his subject four writers who lived during the Transcendentalist movement in New England in the mid-nineteenth century. This was a movement that emphasized the basic goodness and decency of people, and organized religion and government were seen as a threat to that purity. Ralph Waldo Emerson, the subject of the first movement of the sonata, crystallized the general feeling of Transcendentalism in an 1836 speech: “We will walk on our own feet; we will work with our own hands; we will speak our own minds… A nation of men will for the first time exist, because each believes himself inspired by the Divine Soul which also inspires all men.”

Of the four writers, Emerson was the most important to Ives. This is evident in the fact that the Emerson section of the sonata also existed as a piano concerto and an overture, and that Ives continuously tinkered with this movement, claiming that it was never quite finished. Ives focuses on Emerson’s sense of inspiration and thought process, in which jumbled ideas work themselves out and lead to some kind of insight.

Nathaniel Hawthorne is an odd choice of subject for the second movement, since he was actually opposed to Transcendentalism. He believed all men were inherently evil, and most of his stories focus on Puritan guilt. Thus, he serves as sort of a foil.

The third movement is titled “The Alcotts”, referring to Louisa May Alcott and her family. In the context of the sonata, this represents the idea of simple living; Louisa’s parents were involved in a Transcendentalist community living experiment called Fruitlands, and Louisa’s literature illuminates the joy of the common life.

Finally, Ives closes with a movement based on Henry David Thoreau, who also valued simple living but took it to the extreme, retreating into nature for a prolonged period. By ending with Thoreau, Ives makes the intriguing statement that perhaps the answers to some of life’s deepest questions lie in nature.

As an outgrowth of the Transcendentalist philosophical context, Ives’s musical language is a kitchen-sink, anything-goes kaleidoscope of sound. In some sections, massive dissonant chords scream from the keys, while other quiet dissonances evoke distant church bells or other faraway sounds. Snatches of ragtime, jazz, and patriotic tunes appear in Hawthorne, and several motives and tunes pervade all four movements. The level of motivic saturation surpasses Beethoven (and often includes fragments of Beethovenian themes!) and the motivic transformation travels through dozens of psychological implications, taking Liszt’s Sonata in B minor to the next level. The piece traces a path from extreme dissonance and density to absolute clarity and tonality at the end of the Alcotts movement, before returning to austerity for Thoreau.

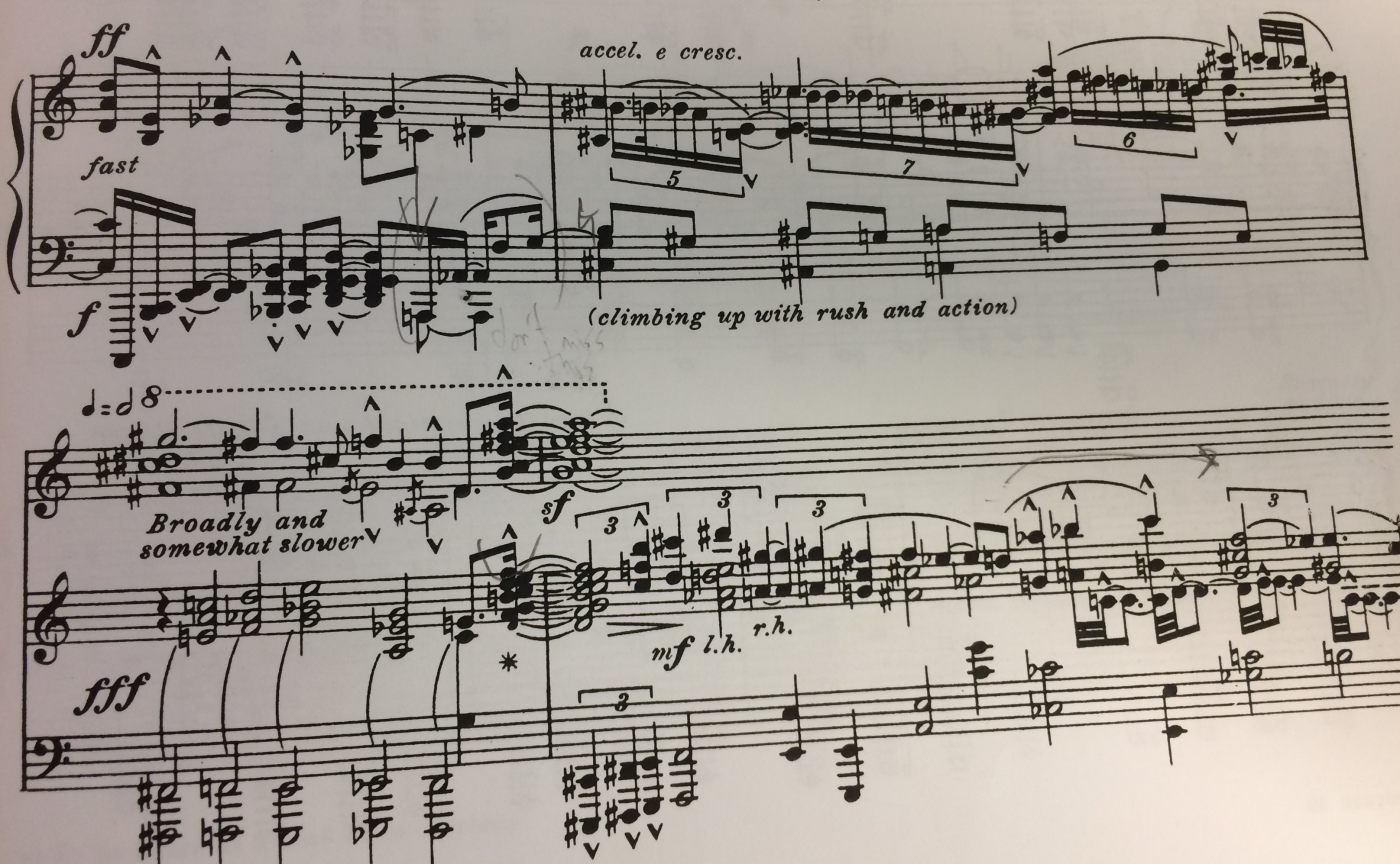

From a performance standpoint, the Concord Sonata presents a unique set of challenges. Any serious performer approaching the score is likely to be baffled by Ives’s footnote in the back material of the score: ‘…there are many passages to be not too evenly played and in which the tempo is not precise or static; it varies usually with the mood of day…a metronome cannot measure Emerson’s mind and oversoul, any more than the Concord steeple bell could’. The writing is dense, often notated in three or four staves, often without barlines, and a certain Yankee ingenuity is required to account for every note in Ives’s massive chords. In keeping with the Transcendentalist spirit, the sonata is intended to be a virtuosic tour de force, an American answer to Beethoven’s Hammerklavier. Indeed, the piece rivals Beethoven’s great sonata in its exploitation of the full expressive capabilities of the piano, including extended techniques. The second movement contains passages of tone clusters to be played with a strip of wood, as well as palm cluster chords, and the final movement contains a passage for a solo flute to play offstage.

Now I’ll attempt a movement-by-movement description of the music. Deep breath.

The Emerson movement is in some ways the most challenging for the listener. It explodes from the outset with dissonance and polyrhythms, with many of the themes stated simultaneously or hidden in the texture before being revealed individually. These themes are:

-the “human faith” theme: an almost-pentatonic tune representing the goodness of common people, sometimes appearing as just its first four notes

-the “Emerson theme”: a short motive with dotted rhythms, conveying strength and purpose

-Beethoven’s Fifth: the famous ta-ta-ta-TA motive we all know, appearing probably over a hundred times over the course of the piece

-Beethoven’s Hammerklavier: a reference to the opening gesture of the first movement of the piece; sometimes Ives states the two Beethoven motives together as a unit

-“pastoral theme” (my given name): a peaceful melody that contains some descending pentatonic scales, sometimes stated as its first four notes (Do-Mi-Mi-Re)

-“development theme”: an angular motive that saturates the “development” section in this movement

-descending chromatic scale: a descending line, usually in octaves in the bass, and usually giving weight to climactic points in the music

So what if I told you that all those themes I mentioned appear in the first thirty seconds of the movement, and are barely recognizable in a chaos of dissonant sound? That’s Ives trying to capture the spirit of Emerson: a whole stack of inter-related ideas, packed with meaning but needing to be slowed down and processed. Ives proceeds to do that, traveling through a variety of moods and presenting intriguing combinations of the different themes. A highlight for me is when he sets the Emerson theme tenderly in C major with some added tones, and then in a denser texture where the theme takes on a hornlike character (indeed, this was a horn solo in the original version for piano and orchestra). When Ives gives the “pastoral theme” its own moment, in a beautiful, soulful harmonization, it’s the first moment in the movement that the listener can relax. Of course, cantankerous Ives disrupts the peace with a new explosion of dissonance and a spicy new harmonization of the Beethoven motives, building to a climax. The pianist Jeremy Denk, a notable performer of this piece, describes Ives’s usage of Beethoven’s Fifth as “dirtying it up and taking it to the streets”. I love it. Part of Ives’s artistic manifesto expressed in the piece is to shake up the concert hall. This was a guy who loved baseball and had colorfully savage names for composers and critics that he disliked.

On page 8 of the score, Ives offers an endnote: “Here begins a section which may reflect Emerson’s poetry rather than the prose.” This remarkable passage features ascending tones of the harmonic series in the left hand, with another pentatonic-ish construction in the right hand, creating waves of resonance. Dissonant notes poke out of the right hand melody, but with a steady pedal bass on C and static harmony, it all “rhymes”. The last bar of each six-bar segment dips into F major before the return to C, creating a bluesy IV-I cadence. The second stanza (if you will) of this material is faster, with more complicated arpeggios in the bass and some new chords in the right hand. This builds to a blazing-bright C major, even faster, with running accompaniment. Now we’re flying over the green hills and forests of New England. Ives follows the poetry section with one marked “prose,” quiet and delicate. Of course he interrupts the reverie again, launching a frantic quasi-fugue with the “development” motive. I’ll spare the details of how it all develops, but it arrives at a prolonged, powerful climax using multiple themes, before melting into a recapitulation proper of the pastoral theme. One final build, of enormous complexity, reaches the true climax of the movement, with the Emerson theme, Beethoven fragments, and others ringing out triumphantly, even defiantly. Ives winds down with more meditation on the Emerson theme, with the chromatic descending scales ever-present in the bass. This part is pretty amazing. By the last page, Ives includes some optional added dissonances in the bass, which extend the harmony even further; it feels like Ives’s language could go on forever, layering more levels of expressive dissonance. The last thing we hear is a final slow Beethoven Fifth motive and a delicate last echoing chord above it, marked pppp. The movement ends, appropriately, in mystery and wonder.

If Emerson was focused on thinking and introspection, Hawthorne is the movement that steps outside to look at the town of Concord. This music lurches from scene to scene, constantly moving forward. Ives extracted much of the music from his piece The Celestial Railroad, based on the Hawthorne story about Christians trying to reach Celestial City (as described in Pilgrim’s Progress) on a train that claims to offer an express ride, skipping all of the hard work and sacrifice of truly following Christ. He also reused a lot of this material in other pieces like the “Comedy” movement of his Fourth Symphony, and in “Putnam’s Camp” from Three Places in New England. Despite my earlier mention of Hawthorne’s focus on guilt, Ives himself stated in the Essays that “this fundamental part of Hawthorne is not attempted in our music (the 2d movement of the series) which is but an extended fragment trying to suggest some of his wilder, fantastical adventure into the half-childlike, half-fairylike phantasmal realms.” There is so much event in the movement, and so much that depicts these specific fantastical images, that, for a real analysis, you’d be better served by reading both Ives’s Essays and seeking out Kyle Gann’s book Charles Ives’s Concord: Essays After a Sonata. Among a few notable moments: a section where the pianist plays soft tone clusters in the upper register with a block of wood, a gentle hymn tune that is twice interrupted by storms of running notes, and an extended groovy ragtime section that ends in fist clusters pummeling the piano. After the fist clusters, Ives devotes the rest of the movement to a sort of fantasia on the patriotic tune “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean,” whipping the music into a nonstop vortex of doom where familiar motives fly past at light speed. The last three pages of the score are so complex, considering the time they were written, that it seems a miracle that they exist.

The Alcotts is a small tonal jewel in the center of this sonata. You might recognize the opening phrase as the introduction from Bruce Hornsby’s song “Every Little Kiss”; now you know where that came from. Ives slows things way down, with a lush A-flat pad underpinning some clearly-etched renderings of the “human faith” theme and the Beethoven fragments. Then he moves on to some more excited murmurings, bursting into raucous statements of the Beethoven Fifth. In the essay about The Alcotts, Ives mentions the spinet piano in the Alcotts household “on which Beth played the old Scotch airs, and played at the Fifth Symphony”. Here he makes the connection between the simplicity of the New England household and the revolutionary spirit of Beethoven, because in the nineteenth century, a typical American’s first experience with the classical canon would be not in the concert hall, but in the home. In this way the seemingly plain lifestyle of these people touches on something bigger, more immense, even divine. The chunky Beethoven-Fifth banging could represent an amateur pianist’s attempt to tap into the transcendent effects of that great symphony. And the Scotch Airs? Well, we get that next, in a passage of great nostalgia. Every time I play this part, no matter where I am, I think of home, of playing Ives on a temperamental, out-of-tune upright before dinner. Again the music gains excitement and energy, crescendo-ing with church bells sounding in the bass, up to a grand statement of the “human faith” theme in C major, richly harmonized, leading to the Beethoven motives. It’s a truly triumphant moment of arrival, and this quotation from the essay summarizes the effect: “All around you, under the Concord sky, there still floats the influence of that human faith melody, transcendent and sentimental enough for the enthusiast or the cynic respectively, reflecting an innate hope— a common interest in common things and common men—a tune the Concord bards are ever playing, while they pound away at the immensities with a Beethovenlike sublimity, and with, may we say, a vehemence and perseverance—for that part of greatness is not so difficult to emulate.” As part of his artistic philosophy in the piece, here Ives also makes a case for tonality as an arrival point. After two movements of hardcore dissonance, the climax in C major feels incredibly majestic, because it is earned.

The sonata probably could have ended there in a satisfying way, but C major is not the end. Ives then takes us to the quiet, slow-paced natural world of Thoreau, where echoes sound over Walden Pond (located in Concord, MA) and thorny lines wind like tangled vines of undergrowth. According to Ives’s essay, the narrative here is of a man walking through the woods, enjoying the peace, but then becoming wrapped up in anxious thoughts of the day. The woods implore him to relax and match the pace of nature. In Ives’s words: “he must let Nature flow through him and slowly; he releases his more personal desires to her broader rhythm, conscious that this blends more and more with the harmony of her solitude.” This cycle occurs a few times and then Ives brings in a new theme, which some analysts call the “walking” theme. It’s deliberate, meditative, and set over a very open bass ostinato of A-C-G. After more developments and events, Ives states the “human faith” theme over quiet dissonances, then over the “walking” theme. Pianists viewing the score for the first time may balk at the word “Flute” over a top staff, but Ives isn’t joking. He gives the option to play the notes in the piano, but in an endnote he writes “Thoreau much prefers to hear the flute over Walden.” It’s admittedly a really neat effect. After the flute cuts off, the piano states the “walking” theme once more, then a gesture that recalls the very opening of the movement. A series of open fifths in a high register sound like the beginning of the Beethoven Fifth theme, but instead of ending on the expected downward skip, he gives us four of these chords in a row. The very last gesture of the sonata is a final dissonant murmuring in the left hand, which works perfectly because the beating of the dissonances makes the chord feel alive, pulsating from the piano. The piece is mysterious, ambiguous, and open-ended even at the conclusion.

The psychological depth of the Concord Sonata continues to astound me. Ives dared to portray elusive thought processes in music and to ask fundamental questions about the meaning of life itself. And the fact that the Concord Sonata still sounds radical to our ears today is a testament to Ives’s imagination and artistic courage. The musical language and progressive piano writing is not a gimmick but an honest outgrowth of the programmatic context. Even as some chords sound completely haphazard in their construction, they are so incredibly specific that sometimes when I discover I’ve been playing a wrong note (or leaving one out) in a chord and correct it, the chord has a totally different aura. Ives’s constant use of contours or melodic fragments that resemble, but don’t quite resemble, the primary themes, means that there’s a subconscious cohesiveness to the material. To quote Ives: “Vagueness is at times an indication of nearness to a perfect truth.” With this in mind, a pianist or listener can spend years trying to track down even the most abstract thematic references, work that into their interpretation in performance (hence a wealth of highly individual recordings), and expand their personal understanding of the piece. The Concord sends continuous ripples of meaning and revelation outward to everyone who engages with it. That’s why I think it’s the greatest sonata, not just of the “contemporary” period, but arguably of all time.

Where to find it (please do):

HL50224180 Ives: Sonata No. 2 (2nd ed.) Concord, Mass 1840-60 (Associated Music Publishers, Inc.)

Note: I love many different recording of the piece for different reasons. Aside from the Drury performance I linked to, here are a few recommendations:

Donna Coleman – deliberate, dark, thoughtful

Marc-André Hamelin – astounding virtuosity

John Kirkpatrick – the original

Brendan, This is remarkable piece, in so many ways. I know well how close Ives and this sonata are to your heart, and how you have lived with it and inside it for so long now. So I am not surprised by the passion and the depth of knowledge you display here. But even with a passionate writer, such an article, considering the subject matter, could easily lose a reader less enthralled with the material than oneself.

You have managed to keep us engaged from start to finish with elegant prose, passion, humor and beautiful technical musical explanations and just enough humanizing background details about the piece and the creator to whet our appetite to know more. This could be a primer for a freshman course in the transcendental movement, too.

I enjoyed the reference to our terrible (that is being charitable) spinet piano and apologize for all the ways that instrument must have frustrated and bedeviled you for so long! When you do think of that piano, I hope it is with at least a little fondness.

Congrats on a stellar piece of work. I can’t wait to read your next masterpiece. Look forward to listening to your next composition, too. No pressure.

Love, Dad

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike